On the Classification of Classical Music

One of the greatest barriers to entry into classical music is terminology. An absurd number of words specific to this genre simply do not exist in the broader cultural zeitgeist. Jazz, Country, Hip-Hop, Rap, Indie Pop, Pop Punk, Metal - all these terms have a prominent enough place in societal awareness that they need little to no explanation when presented on their face. The same is true of most other forms of art. A bookstore or library can be relatively easily navigated via keywords: fiction, non-fiction, history, historical fiction, poetry, cookbooks, philosophy, young adult, etc. Even art museums, with as long and complex a history as they present, tend to be relatively approachable, with potentially foreign terminology clearly explained on placards for anyone requiring further explanation.

So why is it that when I use the word "concerto" with those unfamiliar with classical music, I typically receive blank stares? This question is not meant to be judgemental. I know that classical music holds a lower place than literature and typically than visual arts in most public (and private) education settings. It seems, though, that the concepts we use to categorize classical music are inherently more difficult to grasp without a great deal of study or exposure. As nice as it would be to say that audiences should just be able to listen and enjoy without needing a full tool belt of terminology at their perusal, it is a researched fact that human beings crave categorization. As a species, we are constantly on the hunt for patterns and connections. In addition, these categories are so often used to put together programs, and resultingly help potential patrons decide what concerts they would best enjoy. We must consider a more flexible system of categorization that relies less on terminology but can still be used by those "in the know" and academics alike with subtlety.

In this article, I will propose a spectrum that can be optionally separated by 9 quadrants, on which we can map classical music and all music as a whole. Using a spectrum allows us to be able to chart a listener's tastes, and connect the dots to other kinds of music they might enjoy. The chart I will use is demonstrably related to Flow Theory, so as to enhance the versatility and usability of said connections, as well as to provide opportunities for useful academic study. Before introducing this new potential method for classification and categorization, it is worth exploring the terminology and systems most commonly used, in the past and present, to categorize classical music.

Methods of Categorization

Most commonly, we divide classical music into 4 time periods: Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and Modern. Recently this list has been expanded to Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic, 20th Century, and Modern, but this is already overwhelming and tends to put off casual listeners. The recently released Apple Music Classical app is evidence of chronology being the most pronounced method, as they commit an entire series of hour-long listening guides to each standardized time period and its music. While this is definitely one of the most approachable methods we have to date, the modern era of music composition, along with the ongoing rediscovery of huge swaths of music from the past, has complicated its usefulness going forward. Not only do we have to increase the number of categories as time goes on, making it increasingly complex to understand, but we also live in an age of divergent styles of composition (and have since the 20th century) where music can not be defined by the era it is being written in.

The result of this fracturing in musical styles is what musicologists often jokingly refer to as the "-isms." These -isms may refer to methods of composition such as Minimalism, Serialism, Impressionism, Postmodernism, etc. -Isms can also describe a quality of composition that insinuates one of the aforementioned chronological periods of music, such as Romanticism or Classicism, or a modern twist to said styles with terms such as Neoromanticism or Neoclassicism. There are also -isms that interplay between the two or outside of them, such as Wagnerism, Polystylism, Pastoralism, or Primitivism. As you can see, the -isms get crowded rather quickly yet largely only refer to music written in the 20th century or later. While it may be interesting to study some of these concepts and how they have developed within their own individually constructed spheres, they provide a poor method of categorization for the average consumer of classical music.

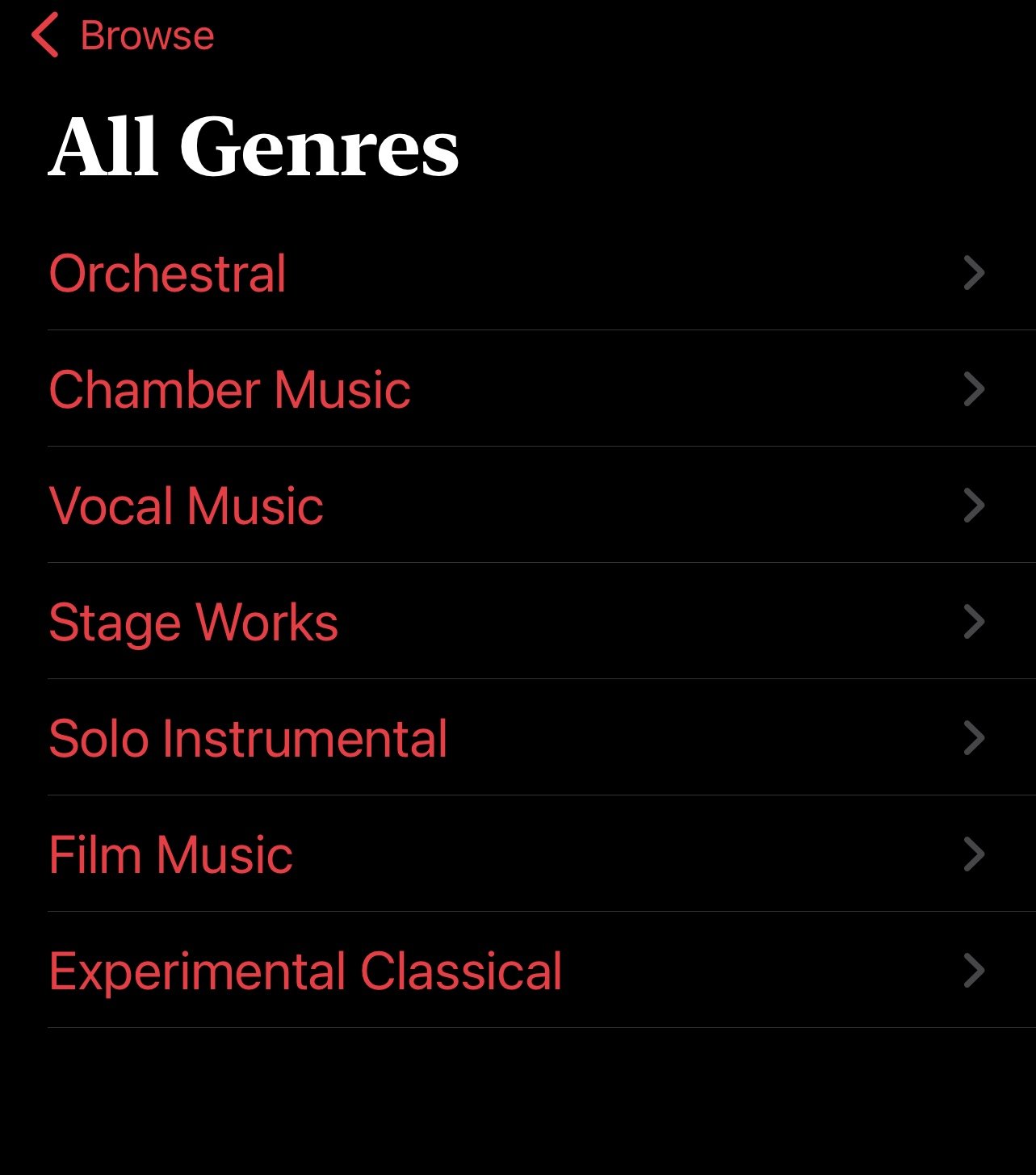

There have also been many recent attempts to define classical music according to sub-genre, but these are terribly inconsistent and usually unclear. Again, the new Apple Music Classical app gives us an example of this:

Classical music streaming site Idagio also attempts to include sub-genres, but are quite different and again have almost nothing to do with listener tastes.

Once upon a time, it was good enough to divide music into two categories: secular and religious. How music was divided this way was based entirely on the intended audience. For example, the Cantatas of J.S. Bach were specifically written for worship services within the Lutheran church and therefore would be considered religious. His Brandenburg Concertos, on the other hand, were written for a court audience and had no direct religious affiliation, thus would be considered secular. This divide was clearly maintained for many hundreds of years, especially during the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods, until the first examples of religious music being performed for secular audiences in concert halls occurred.

As the barrier between religious and secular music began to break down, it became more appropriate to refer to a piece of music's form or formal style. There was a rapid proliferation of Opus numbers and terms such as String Quartet, Symphony, Sonata, Divertimento, Prelude, Partita, etc., as well as a Modus Operandi of what kinds of music - in structure and scope - these titles represented. These forms became rather set in stone throughout the Classical and early Romantic Periods by the likes of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Brahms, but as time progressed, composers yearned for the freedom to tell more overt stories through their music. They created new words, titles, or descriptions, such as Schubert's Impromptus, Chopin's Ballades, Schumann's Fantasies, and Romances, or even Berlioz's half-symphony half-viola concerto "Harold in Italy." By the time Mahler was composing, his "Symphonies" simply couldn't be put in the same category as the symphonies of Mozart or Haydn, and Richard Strauss was writing symphonic works on a scale larger than Beethoven that weren't even called symphonies. In the modern era, "String Quartet" hardly ever means a four-movement work written in the template of Haydn. Meanwhile, as early as the late 19th century, a Cantata could be written about any kind of topic, religious or not, with widely varying orchestrations. These terms no longer have the power to hold the variety which is attributed to them. So where do we go from here?

Putting Music on the Grid

To facilitate the maximum value of a new method of categorization, I will use a model inspired by Flow Theory. Flow Theory is a popular psychological theory from the 1970s that quickly became multi-disciplinary that typically concerns human activities that involve skill and challenge. Originally posited by the researcher Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow Theory suggests that humans thrive and find satisfaction within the specific category of "Flow," where a person's skill in a given activity matches the challenge presented, and not above or below, creating a state of being in which the person feels focused and satisfied. Flow Theory was born out of the question, "What is enjoyment?" and resulted in practically an entire field of study on methods in which humans achieve this state of existence. This is not the same thing as an emotional reaction but instead has to do more with neural activity. Typically, it is achieved through action rather than stasis, and it is the balance of having hurdles to overcome and being able to overcome those hurdles that bring us into a "Flow" state. Coming into this routine of challenge and overcoming challenge allows us to become completely absorbed in an activity and achieve maximum focus and heightened brain functionality.

There has been some limited research done on how listening to music can help an individual achieve a Flow State, but music and flow in general have close ties and have had since the theory was first published. So what if we took the basic visual representation of Flow by Csikszentmihalyi and shifted it to create a map on which we could place pieces of music and thus find commonality based on the level of Flow achieved? In making this shift, we must also put the responsibility for flow on the music itself, rather than the skill of the listener. The goal here is not to argue that certain music requires more or less of the listener, although that may indeed be the case in other contexts, but that it can be traced to a specific point on a spectrum based on the factors of Complexity and Rigidness, and that these factors may, in fact, have a similar effect on the listener in achieving a state of Flow, or if used purposely (or accidentally) by the composer in a different way, incite boredom or anxiety in the listener. Therefore, we must see the structure of a piece to be a challenge to be overcome by its layers, whether they be simple or complex. In other words, if a piece has rigid structures, more complexity must be provided to make up for its Rigidness. If a piece has loose structures with little for the listener to hold onto, the composer must provide simplicity in order to give the music an inherent state of flow. When balance is achieved, it may be appropriate to attribute a state of flow to the music.

Understanding the Grid

As you can see above, we will replace Skill and Challenge with the concepts of Complexity and Rigidness. Complexity is a measure of how many layers exist within the music and how easy or difficult it is to decipher those layers, and Rigidness is a measure of how "accessible" the music is (for lack of a better word) to a listener in terms of tonal, phrasing, and general structures. Thereby, if a piece of music has a rigid structure and simple layers, it could prove to be boring. If it has a more loose and improvisatory structure and complex layers, it could prove to be overwhelming and potentially even anxiety-inducing to the listener. The reason why Complex and Rigid intersect at the 90-degree angle is that those are the two most common traits, historically, in classical music. It is largely a highly layered yet formally rigid art form, and while this is not always the case it is safe to say that an enormous portion of the "Cannon" in particular can be found around that intersectionality.

One could use the metaphor of a house: rigidity refers to what the house is made of, how sturdy it is, how many corners vs. rounded edges it uses; or in other words, what shapes, angles, and materials may be used to create the overall structure of the building. Complexity then refers to the interior design and layout of the building: is it a predictable layout that is intuitive to get around? Are there many hallways or some secret passageways? How many items and pieces of furniture can you find in the building and how uniform are said items?

By studying the balance of these two elements, we can map and categorize music across time. In theory, then, an individual listener can discover what region of this chart lies the music they most enjoy listening to and resultingly expand the amount of music they may have otherwise been exposed to with more restricting or less helpful categorical criteria. Individuals will also vary on the size of the region that fits their tastes, as well as the number of different regions, as it would be expected for there to be multitudinous gaps for each listener. This chart can also easily cross the boundaries of genre, so if an individual is interested in a new or foreign genre but has established tastes within another, they might already have a starting point upon which to ground themselves.

In addition, this chart provides a methodology for future study of Flow Theory from a listener's perspective. Most studies on Flow Theory and listening to music do not discuss in depth the types of music chosen for the studies, and it is absolutely beyond question that, with the enormous variety of music available in the world, there should be variation in which kinds of music would facilitate a state of Flow more generally as well as on a personal level. The research possibilities for this are valuable and would be relatively simple to construct and execute.

A numerical system cannot be applied to Complexity and Rigidness, as they are in themselves complex characteristics. However, each one can, in itself, be boiled down to a balance of two main characteristics. Complexity can be measured based on density and the repetition of material.

Density is mainly based on the number of voices present. For example, Bach's three-part inventions would be considered denser than his two-part inventions. Or for a more nuanced example, a texture with one harmonic voice and one melodic voice would be considered less dense than a percussion texture with five or six different rhythmic qualities. The reason we have to call this density vs. just the number of voices is that we must take into account other criteria like timbre, resonance, and in the case of electronic or pop music things like reverb or other sound modifiers. For example, an orchestral fugue may be technically only with four voices, but the timbre will likely change much more frequently than a four-voice organ fugue. Density does not only refer to how often the timbre changes but also how many different timbres are happening at once, as well as different lines.

On the other end, we have the repetition of material, or, more specifically, the exact repetition of material, including its density. Exact repetition could be used purposefully to simplify a piece with little structure or a high level of density, or it could be avoided to add complexity. The less a listener hears a specific theme, melody, texture, rhythm, etc., the more complex will feel (although not necessarily be) to understand. Most commonly, a composer will use repetition to a limited extent in order to establish a pattern that can then be subverted and create interest.

Rigidness can be measured based on levels of tonal ambiguity and formal structure.

I hesitate to use the term tonal ambiguity as it sounds more Eurocentric than I would like for this chart to be, but ultimately the term as it is used in this context refers to the use of a consistent tonal language insular to any given piece of music, and additionally how wide of a vocabulary is used within that tonal language. Traditional Western harmonic structures, for example, live within their own tonal language, but composers over the years have managed to manipulate this language in many ways to create varying degrees of ambiguity (i.e. tricking the listener with cadences, chord progressions, or key changes that may be unexpected based on set expectations, similar to how a composer will use repetition to set a standard that is meant to be broken). The same is true in any other tonal language, whether it be microtonalism, 12-tone, Renaissance-style counterpoint, Gamelan tonalities, or the West African talking drum. Tonal ambiguity, therefore, refers to what how established protocols within a work or sometimes within a given tonal style are established and/or broken down before the listener's ears. If the tonal structures are less established or less subverted, tonal ambiguity increases.

Formal structures can be thought of in a similar manner, but rather than the tonality of the piece it refers to its micro and macro structures. For example, if you watch a house being built, as soon as construction begins one might be able to guess at the kind and style of the structure. Once the foundation is poured you may be able to guess at the size and scope of the home being built. As more elements are added, you can make further estimations: how many bedrooms, where the entrances might be, will it have a garage or steps leading up to it, etc. During this process, the observer's expectations might be subverted: suddenly a large dome is attached and you wonder if it will be a church or a giant greenhouse. More and more stories are added and you begin to realize it is an apartment complex and not a home. In some rare cases, it may end up being a totally novel architectural design that the observer has little to no reference point for understanding it.

Formal structures in music are experienced in a similar way. Upon hearing the opening of a piece, the listener might start to guess at its structures right away, and as it develops it will become either more or less clear. Almost all music has some structure, but the degree to which it is observable is widely varying. We also can observe these structures on a smaller scale: is a phrase fairly predictable in its structure, and if so it ever changed to subvert expectations and generate interest? This is what we mean when we discuss formal structures in this context. In addition, in music that involves text, the structure of the text should be taken into account, i.e. are the words esoteric or fragmented, or do they follow a story or framework with observable patterns or direction, as described above concerning musical structures?

Laying Out the Map

The nuance and debatability of these relationships are infinite, therefore for some applications of this system of categorization, we require a system of 9 quadrants in order to simplify the process. This is extremely useful in grouping large quantities of music into similar groups in order to explore their similarities and differences from the other groups. The categories can be mapped out as such:

It has been suggested that a large portion of music from the Baroque, Classical, and Romantic periods falls in the Rigid-Complex or the Common-Common quadrants. Indeed, this is theoretically the ideal lane to facilitate in the music an inherent state of flow, although it is surely possible that, depending on the individual, any of these quadrants could aid an individual to achieve flow. Loose-Complex music would tend to be overwhelming to a listener and provide little tangible material to follow, while Rigid-Simple music would potentially be considered boring or of little creative value (not that this is actually true, but for the sake of the thought experiment it would most likely be a very widely accepted as true).

Grouping music in this manner is less than ideal to me, but perhaps necessary in some contexts. Ideally, this graph should be treated more as a color wheel, where specific examples fade infinitely into the next. But using quadrants does open up the ideal for more rigid testing of this theory - does this method of categorization have a higher rate of success helping a listener find music they enjoy than other kinds of groupings like time periods or sub-genres? If we were to group music to this extent, the theory would be much less likely to prove accurate, but I might argue it would still be a superior model to those mentioned previously.

Examples

Let us use the First Movement of Beethoven's 5th Symphony as an example to explore the concepts held in this graph. In this example, there is an extreme amount of repetition, particularly of the infamous 4-note motif found throughout, complimented by a fairly large number of voices. After the initial unison, there are 3 competing voices, quickly expounded upon with other voices joining and receding throughout creating a rich tapestry of sound. Therefore, one could consider this work could be middling in terms of complexity based on the relevant criteria. Meanwhile, it has a rather strict degree of formal structure with a few unique moments, such as the famous oboe cadenza in the recapitulation, and some basic level of Tonal Ambiguity provided by the simplicity of the main motive and Beethoven's creativity creating and then subverting harmonic expectations. Therefore, overall, this work lands to the right of the middle and slightly up on our original grid, in the upper part of the Rigid-Common quadrant, perhaps just within the path of "Flow."

So the question then becomes, other than another Beethoven symphony, what else lies in this region of the grid? Perhaps Philip Glass' String Quartet No. 3. Its complexity is similar: 3-4 voices throughout, so about the same as Beethoven's symphony, and it has a fairly extreme repetition of materials. The complexity would probably match that of Beethoven's, though, because the layers themselves are less defined. As far as Rigidness, the roles of tonal ambiguity and formal structure are switched from Beethoven's 5th symphony: there is less tonal ambiguity as the chordal material is always fully fleshed out and set in a particular harmonic location, but there is a less clear formal structure to the music. Therefore, according to this theory of categorization, someone who found a state of Flow listening to Beethoven's 5th Symphony would very likely also find a state of Flow listening to Glass' 3rd String Quartet.

What if we took a potentially more intimidating work such as Messiaen's Turangalîla-Symphonie, an 80-minute and 10-movement long work that features an enormous orchestra with unusual instrumentations, such as a solo piano and an Ondes Martenot (an early electronic instrument)?

The size of the orchestra and the intricacy of the writing makes for a dense texture throughout, but the complexity is balanced out by its repetition of material. There are four main themes used throughout all ten movements, along with themes unique to each movement, but almost every texture you hear is repeated, giving the listener a chance to grasp and understand everything that happens. Considering this, I would conclude that the layers of this work could be placed in the Common quadrant. On the other side of the chart, this work's tonal ambiguity, as well as its formal structure, both fall very much in the middle of their respective spectrums. Overall, this piece lies in the middle region of our chart, in the "Common-Common" sector.

Typically, we would look to other mid-twentieth-century symphonic works for comparison, but what if we could use this system to find a more interesting yet reliable pairing? Another example would be the majority of Richard Strauss' tone poems written 50 years earlier than Turangalîla. Ein Heldenleben is an expansive tone poem, also for a large orchestra with complex harmonic structures and a variety of themes that either exist within a specific section only or are repeated throughout the piece. While the number of voices changes frequently, considering the overall work there is generally a high level of density. Much of the thematic material is consistently repeated throughout, putting Complexity middle-ish on the spectrum. Similarly, both tonal ambiguity and formal structure are fairly centered, as it is a grand work with a clear plot, and while lush and often quickly changing harmonically, it also establishes itself well before moving through harmonically. Overall, this places Ein Heldenleben very close in region to Tangalîla-Symphonie.

Nearly 130 years later, the recently released recording of Thomas Adès' Dante provides yet another work that lies in the middle of the chart. It is also centered in tonal ambiguity, perhaps slightly leaning to the more ambiguous with an overall surprisingly conventional and understandable ballet structure, a high level of density with a heavy use of repetition. All three of these composers and pieces use wildly different styles and compositional techniques over a 130-year timespan, but I would argue that they all cater to a similar taste.

What if we take it a few more steps, looking at a piece like St. Matthew's Passion by J.S. Bach? While it is also fairly dense, its orchestration is smaller than the other works we have examined. The complexity is balanced out by its overall lack of repetition (each individual movement has some repetition but across the entire work there is almost none) putting it near the middle. It is also less tonally ambiguous than the other two works (while it is still pretty gnarly at times, it establishes tonal expectations more than it subverts them) but relies less on overt formal structures, and the structures it does lean on tend to be rather improvisatory by nature, with the exception being the arias which tend to be in a very understandable ternary form. Overall, this work would probably land on the chart slightly below Ein Heldenleben, Turangalîla-Symphonie, and Dante, but far closer to them than any other method of known categorization other than being a grand orchestral work. All of them, though, could be considered Common-Common.

Can we find a non-orchestral work that also fits into this region? Two examples come to mind. Mozart's Gran Partita for 13 Winds could also be classified as Common-Common. With a surprising amount of density and little exact repetition (he is endlessly creative in revoicing and creating variation upon formal thematic material), this music could be considered quite complex. In terms of formal structures, one could argue that - while it does rely on conventional forms within each movement - much of the formality around small-scale structures such as phrasing and melody, as well as the large-scale structure of the work as a whole, subverts the listener's expectations constantly. Considering this and the piece's limited level of tonal ambiguity, the work is more than moderately complex and rigid.

If we go back to around the same time that Turangalîla-Symphonie was written, but move to Eastern Europe and back down the orchestration to a string quartet, we can find yet another fine comparison in Bartok's 4th String Quartet. Obviously, the number of voices is limited, but the constant shifting in voicing and timbre creates a moderately dense texture. It also retains a limited repetition of material, as the development of material and its voicing is constant. It has a moderate level of formal structures that are established but only to a degree for the listener, with rhythmic and phrasing irregularities but thematic consistency, along with mostly understandable movement structures and a conventional overall 4-movement structure.

Again, somehow this string quartet for four voices can be closely paired with Bach's St. Matthew's Passion, Mozart's Gran Partita, Strauss' Ein Heldenleben, Messiaen's Turangalîla-Symphonie, and Adès' Dante. This is not a typical playlist you would find on Spotify or Apple Music, but I would argue strongly that a listener who finds a state of flow listening to any one of these works would have a statistical probability to respond equally to the others.

Applications

There are some of the more obvious applications for this method of charting music. Some of the first that come to mind are simple, such as using it as a programming tool. Building a program around music that "feels" similar could actually help the audience discover music that is new to them, as they may find a state of flow in a more famous or familiar piece and then surprise themselves by continuing to retain that state. I would argue that programs should be built with more familiar-sounding works at the beginning and the end, and less commonly performed works in the middle so that the state of flow can be retained and the connection can be made at the end - consciously or not - as to what the works have in common with each other. The same concepts could be used to construct effective playlists for streaming companies, retaining the Flow of listeners to both improve retention and expand interest.

This method of classification has great potential as a point of research. We know from previous research that listening to music has the potential to induce a Flow state, but there are many questions that still need answering, such as: A) Does Flow indeed line up to these two criteria of Layers (Complexity) and Structures (Rigidness)? B) Can these criteria successfully cross between genres to encourage a wider palate of listening? C) What other social norms, standards, or restrictions potentially inhibit the use of this method of categorization (i.e. prejudices, preconceptions, anxieties), and how can they be minimized? This area is ripe for thorough academic study in the field of classical music in particular but all music and even art could arguably benefit from it.

The chart has applications in the realm of pedagogy as well. Boiling down composition to a different set of criteria than thematicism, rhythm, and pitch creates an entirely new method of approaching education within this art form. Teachers of composition can have four basic, tangible aspects of a work to point to (tonal ambiguity, formal structure, density, and repetition) when discussing how to construct a "successful" work, and can even potentially, given the criteria really so balance out to create a Flow State or not, give specific advice on what can be changed to fall within the path of Flow if that is the goal of the student. If a composition can learn to successfully manipulate these four facets of music, they will have much more control over the listener's experience of their work.

Perhaps more creatively, though, is applying this chart to algorithms having to do with marketing and advertisement. For example, if you are an orchestra looking to advertise an orchestra concert featuring a Beethoven Piano Concerto, theoretically you could map that piece to the chart above, then after examining the trending albums on various music streaming sites, find a suitable comparison, as this chart works quite well between all genres of music. With that comparison set in place, it should not be difficult to find people who live in the area where said performance will be given, and who listen to the chosen trending song or songs that correlate to your program, and then advertise directly to those people via social media. These are relatively ordinary information purchases and exchanges in today's social media and global technology era but are at a level of targeted advertising not yet utilized by most cultural institutions.

Conclusion

The impulse behind building a new method of categorization for classical music is two-fold: 1. to help listeners engage with a considerably wider selection of music without throwing darts at the wall, so to speak, providing a starting point to explore diverse sounds without completely stepping outside of pre-established comfort zones of listening; and 2. to provide a way to assess how the ingredients of music affect its inherent "state" of Flow and its likelihood to invoke a state of Flow in a listener. Each of these applications has been provided with an associated chart, one that shows the ideal path for invoking a Flow state, and the other that divides the criteria into 9 sectors. These charts have been further broken down into four key elements (formal structures, tonal ambiguity, density, and repetition) in an attempt to uncover what factors most contribute to the Structures and Layers of music. My hope for this material in a broad sense is that it might provide a new lens through which we can observe the relationships between various kinds and genres of music, across time, and take away some of the focus on increasingly ineffective methods of categorization. Music is without a doubt infinite, so any attempt at categorizing it is bound to have flaws. Hopefully, though, this might provide a useful stepping stone in rethinking how we group and present music to our collective audiences.